FilmJuice have my review of Thomas Cailley’s hugely engaging teen drama Les Combattants (a.k.a. Love at First Fight). Having received a standing ovation at Cannes, Cailley’s debut film went on to secure nine nominations and three wins at the French equivalent of the Oscars. Celebrated by French critics as nothing less than the future of French cinema, Les Combattants limped onto Anglo-American screens where it was marketed and reviewed as a romantic comedy (hence the stupid English-language title). Given that it is short on jokes and long on the kind of evocative, hands-off storytelling that is common in European drama and absent from the history of romantic comedy, the film received middling reviews from critics who seemed more interested in engaging with the press release than the nature of the film itself. According to Gary Goldstein at the LA Times:

There’s a better movie floating around the edges of the French import “Love at First Fight” than first-time feature director Thomas Cailley has allowed to surface. Though it’s billed as a romantic comedy, this quirky tale takes too many narrative U-turns that seem to dodge the genre’s more traditional (read: satisfying) tropes and dynamics.

There’s misprision and then there’s critical laziness. This is an example of the latter as Les Combattants is actually a fantastic meditation on Young Adult fiction and contemporary gender roles. You just need to make a bit of an effort in order to see it.

Les Combattants is built around two young adult protagonists: ‘ Arnaud whose lack of ambition and focus in no way seems to prevent his integration into a French society that is always pleased to see him. Everywhere he goes, Arnaud is offered jobs and opportunities for advancement despite the fact that the French economy is evidently still in tatters. plays Mathilde, a fiercely intelligent and incredibly driven young woman whose every attempt to secure an education or job is met with dismissive scorn. The fact that Arnaud’s white male privilege protects him from economic deprivation means that he is far better disposed to people and society than Mathilde, who spends the entire film having doors slammed in her face:

When Mathilde joins Arnaud’s family for dinner, the conversation naturally turns to the lack of jobs for young people and we see how the inequalities in French society have nurtured two very different reactions to the economic crisis: Embittered and unappreciated, Mathilde reaches the conclusion that society has nothing to offer her and so sets about preparing for its imminent demise; Pampered and protected, Arnaud has the luxury to consider a number of different career paths and so admits that he has never really thought about the collapse of Western civilisation.

Arnaud slowly falls in love with Mathilde and so decides to join her at a boot camp designed to help young adults preparing to join a parachute regiment. While Arnaud’s easy charm and happiness going with the flow mean that he fits right into a military environment, Mathilde solitary nature and intense disposition mean that the army falls out of love with Mathilde almost as quickly as Mathilde loses interest in the army. Eventually, things get so bad that Arnaud decides to abandon his shot at a military career and simply wanders off into the wilderness with Mathilde in tow.

As I explain in my review, I think that Cailley was wrong to have Arnaud discover his agency at the end of the film. I think that having Arnaud lead the pair out of danger undermines Mathilde’s character and turns Les Combattants from a film about a couple into a film about a young man. This misstep aside, I think this film has a lot of interesting things to say about gender. Particularly when you realise the similarities between Haenel’s intense survivalist Mathilde and the intensely self-reliant young women who feature in books like Suzanne Collins’ The Hunger Games, Veronica Roth’s Divergent series, and Kristin Cashore’s Graceling.

Les Combattants suggests that women have it considerably harder than men in the current economic climate. What makes Cailley’s analysis interesting is the suggestion that these inequalities might well have a knock-on effect of how the different genders perceive society. For example, Mathilde has grown intensely self-reliant because she no longer trusts society whereas Arnaud is happy to trust society and go with the flow because his experience is of people and institutions falling over themselves to offer him jobs and opportunities for advancement. The film’s ending strikes a false note because allowing Arnaud to save the day sends the message that Arnaud’s vision of society is somehow correct whereas Mathilde’s is paranoid and self-destructive. I disagree… I think Mathilde’s wariness is a rational response to an irrational world and I can’t help but wonder whether the immense popularity of YA among women might not be a direct response to their unequal treatment at the hands of society.

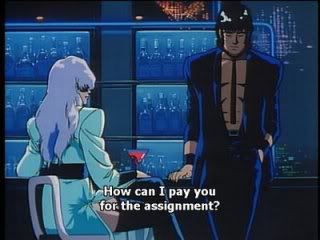

Interesting stuff aside, Les Combattants is one of the better looking films I have reviewed recently, so I thought I would share a few screen grabs: