Joanna Hogg is one of the most exciting film directors working in Britain today. A graduate of the National Film and Television School, Hogg spent the 1990s working in British television on series such as Casualty, London’s Burning and an Eastenders spin-off exploring the wartime exploits of a young Dot Cotton. While a decade behind the cameras of soap operas and disposable dramas does not usually herald the arrival of a major directing talent, it is worth remembering that British soap operas have a long history of social realism meaning that every year Hogg spent on Casualty and London’s Burning was a year in which she got better at observing people and the worlds they inhabit.

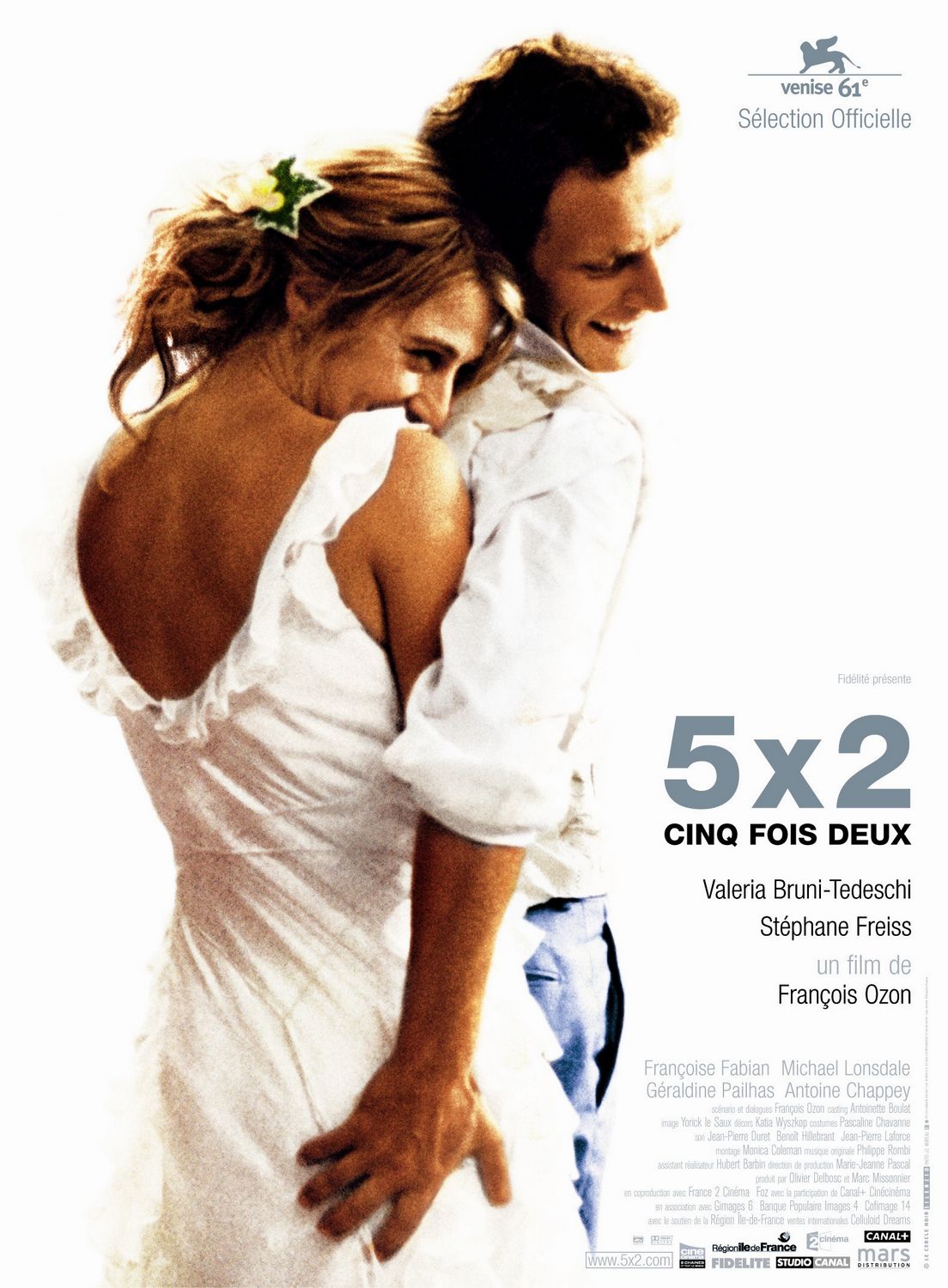

Hogg’s eye for social rituals and group dynamics was evident even in her debut feature Unrelated. The film revolves around a woman who joins her friends on holiday as an excuse to spend some time away from her partner. Upon arriving in Italy, the woman finds herself in a house that is already split down the middle along generational lines and decides to hang out with her friends’ hedonistic teenaged children rather than the people she came to visit. This yields a splendid holiday until a failed attempt at seduction sends the woman scurrying back to the grown-up side of the house and the grown-up life she left in Britain. While Unrelated is a recognisably British film about recognisably British characters who behave in a recognisably British way, the film’s treatment of its subject matter evokes European rather than British cinema. Aside from a southern climate and an interest in middle-aged sexuality that recalls works like Ozon’s Swimming Pool, Unrelated is defined by its emotional ambiguities and a fondness for long dialogue-free scenes and palate-cleansing landscape photography that are common in European cinema but almost entirely absent from British film.

Much like Unrelated, Hogg’s Archipelago is best understood as an attempt to explore the products of British social realism using the language of French art house drama. However, where Hogg’s first film seemed to go out of its way to retain such European topoi as sun-drenched holiday homes and illicit affairs, her second film is far more recognisably British thanks to its focus on wind-blasted landscapes and awkward family holidays. Shot on the isles of Scilly off the South-West coast of Cornwall, Archipelago features a pair of grown-up children who decide to go on holiday with their mother. The family’s unhappiness is manifest right from the start as disagreements escalate into arguments with a speed that suggests the presence of unaddressed problems. However, despite numerous elephants in the room, the family never sit down to discuss their feelings… they simply evade and deflect them by choosing to blow up over ridiculous things such as choice of bathroom and whether or not a piece of food has been properly cooked. Elegantly reserved when it comes to its characters’ actual inner lives, Archipelago is a magnificent study of the British middle-classes and how taboos surrounding direct confrontation and talking about one’s feelings have encouraged people to become emotionally self-contained. The film suggests that while this system of self-containment may be completely unreliable, it is supported by a cultural tolerance of passive-aggressive venting and the kind of extreme emotional projection that would probably be regarded as psychotic in a more emotionally-expansive culture. Like Unrelated, Archipelago explores these ideas in a quintessentially European manner by forcing the audience to observe only to then pull back and provide them with evocative imagery that will encourage them to draw their own conclusions about the things they have just been shown. This willingness to use European cinematic techniques to explore British emotional landscapes not only made for an incredibly fresh cinematic experience, it also served as a timely reminder of how staid, unadventurous and lacking in diversity European art house film can be.

Archipelago is not only a perfect fusion of British social realism and European cinematic vocabulary but also the completion of an experimental journey that began with Unrelated. This posed an interesting question: if Archipelago was everything that Unrelated wanted to be, where would their director go next?

Joanna Hogg’s third film Exhibition is also her most ambitious. Like its predecessors, the film uses a European cinematic vocabulary to explore the emotional dynamics of British middle-class life. However, whereas Unrelated and Archipelago both revolved around relatable characters who were really quite easy to understand, Exhibition concerns itself with a couple whose inner lives are so bizarre and complex that they can only be expressed artistically.