This week saw the release of Arrow Films’ Camera Obscura; a magnificent box set exploring the early work of Polish director Walerian Borowczyk. As someone who already owns quite a few luxurious box sets devoted to art house film directors, you would think that I’d be immune to the packaging-foo of independent DVD publishers but Camera Obscura has taken me completely by surprise. Aside from an impressively thick booklet, the box set contains five beautifully restored feature-length films as well as Boro’s early short films and a suite of documentaries about both him and his work. To say that Camera Obscura is comprehensive would be an understatement, FilmJuice have my reviews of:

- The Theatre of Mr. and Mrs. Kabal (1967)

- Goto, Island of Love (1969)

- Blanche (1971)

- Immoral Tales (1974)

- The Beast (1975)

FilmJuice’s editorial format required me to break the box set down into five separate films, which is something of a pity as Camera Obscura does an absolutely amazing job of capturing Borowsczyk’s development as an artist. The key to this process of evolution are the short films included on the same disc as The Theatre of Mr. and Mrs. Kabal.

***

Made between 1959 and 1984, the fourteen animated short films included as part of the collection are presented out of chronological order. While it is not immediately clear what (if any) order they are presented in, the animations do serve to communicate a single indisputable fact: Boro really was an extraordinarily versatile creator.

Arguably the pick of the bunch is “Renaissance”; a solemn meditation on the cultural and material destruction of the First World War, the film opens with a sustained shot of a burned and broken pile of detritus. After a few seconds, the walls lose their charring as tables, prayer books, musical instruments and stuffed owls pull themselves together into an elegant tableau of 19th Century bourgeois that climaxes with photographs of a middle-class family sitting next to a grenade that promptly explodes, returning the bubble of civilisation to the chaos and entropy from which it sprang.

Also hugely impressive is “Astronauts” the first film that Boro made upon arriving in France. Credited only as a co-director because he had not yet cleared the paperwork allowing him to work, Boro uses stills photography, repurposed lithographs and hand-drawn animations to create a darkly surreal journey through one man’s imagination. Boro shows us the process of inspiration as flies’ wings and horses’ legs combine with old furniture and discarded bits of newspaper to create a flying machine for the film’s pipe-smoking protagonist who uses his new vehicle to spy on his neighbours and humiliate politicians before ensnaring himself in a battle between alien spacecraft.

Also brilliant is “Rosalie”, a homage to Carl Theodor Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc in which a tearful woman looks directly into the camera and tells of how she was seduced by a man and then cast aside by the society that should have been there to help her. Intercut with images of blood stained objects that cut through the woman’s heartfelt pleas and connect us with the horrific reality she is forced to describe, Rosalie shows that Boro could be just as humane and moral as he could be visually clever.

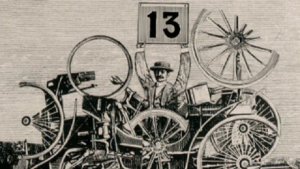

Less striking but perhaps more culturally significant is “Grandma’s Encyclopaedia”. Displaying the same interest in 19th Century cultural detritus as virtually all of the other short films in the collection, this film takes images from 19th century lithographs, modifies them and animates them to tell a story about racing steam-powered vehicles. What makes this animated short so significant is the fact that its methods and iconography are absolutely identical to those immortalised by Terry Gilliam in Monty Python’s Flying Circus. Predating Python by no less than six years, “Grandma’s Encyclopaedia” was undoubtedly a formative influence on Terry Gilliam, something he pretty much admits in the introduction included in the collection.

Another striking visual departure is “Angel’s Games”, a series of barely animated paintings depicting an oddly industrialised landscape full of pipes and smoke recalling the holocaust. Not so much dark as astonishingly sombre and weird, the images summon an intense sense of unease despite the deliberate artificiality of their medium and the abstract nature of their imagery.

Even more bizarre is “Diptych” a gorgeously gritty black and white short documentary about an aging French farmer who works in complete poverty to keep some vineyards alive. Despite the bleakness of the subject matter, Boro manages to inject real warmth and humanity into the farmer’s story. A warmth and humanity that is completely absent from the saturated colours and artificial lighting of the images of kittens and flowers that end the short. It is impossible not to marvel at the cinematic talent of a man who can make gorgeous kittens seem bleak and horrifying while a man working himself to death can seem noble and humane.

Arguably the weakest of the short films included in the collection, “The Concert” was undoubtedly the most time-consuming as it is entirely abstract and hand-drawn. While the film’s title suggests a musical theme, a more correct description would be to say that it is about two weird characters that form and un-form themselves around an attempt to play the piano. Visually striking this film may be as severed limbs dance the cancan, but profound it is not, which is perhaps unfortunate as it also served as the template for Boro’s first feature-length film, The Theatre of Mr. and Mrs. Kabal.

***

When I say that Camera Obscura allows you to chart the evolution of Borowczyk’s career, I am not using the term ‘evolution’ as the prosaic equivalent of ‘get better’ or ‘acquire more skills’. What I mean is that Boro will often experiment with a technique in one film and then re-use it in a later film. This is hardly unusual but Boro’s visual style was so unique that his various acts of recycling and repurposing seem to just leap off the screen, such is their impact. For example, Boro’s “Rosalie” saw him experimenting with Carl Theodor Dreyer’s use of close-ups on human faces and the technique features quite prominently in Goto, Island of Love as it involves the exact same actress in almost the exact same shot. While Boro’s recycling allows you to follow his growing ambition, it also allows you to follow his relative decline. For example, Blanche makes frequent use of footage of people’s feet and hands, as though they are being painted by a Renaissance artist. This technique re-appears in Immoral Tales where it is used to shoot boobies and bushes, suggesting that Boro was just as happy arousing his audience as he was encouraging them to look at cinema in terms of medieval and renaissance art. Lots of box sets allow you to see how a director’s interests changed over time but I think that Camera Obscura is the only one that encourages you to chart a director’s career one cinematic technique at a time.

***

People interested in reading a different (and generally far superior) approach to Camera Obscura are encouraged to go and take a look at Cine Outsider‘s coverage. Taking it disc by disc, Slarek has thus far written about: