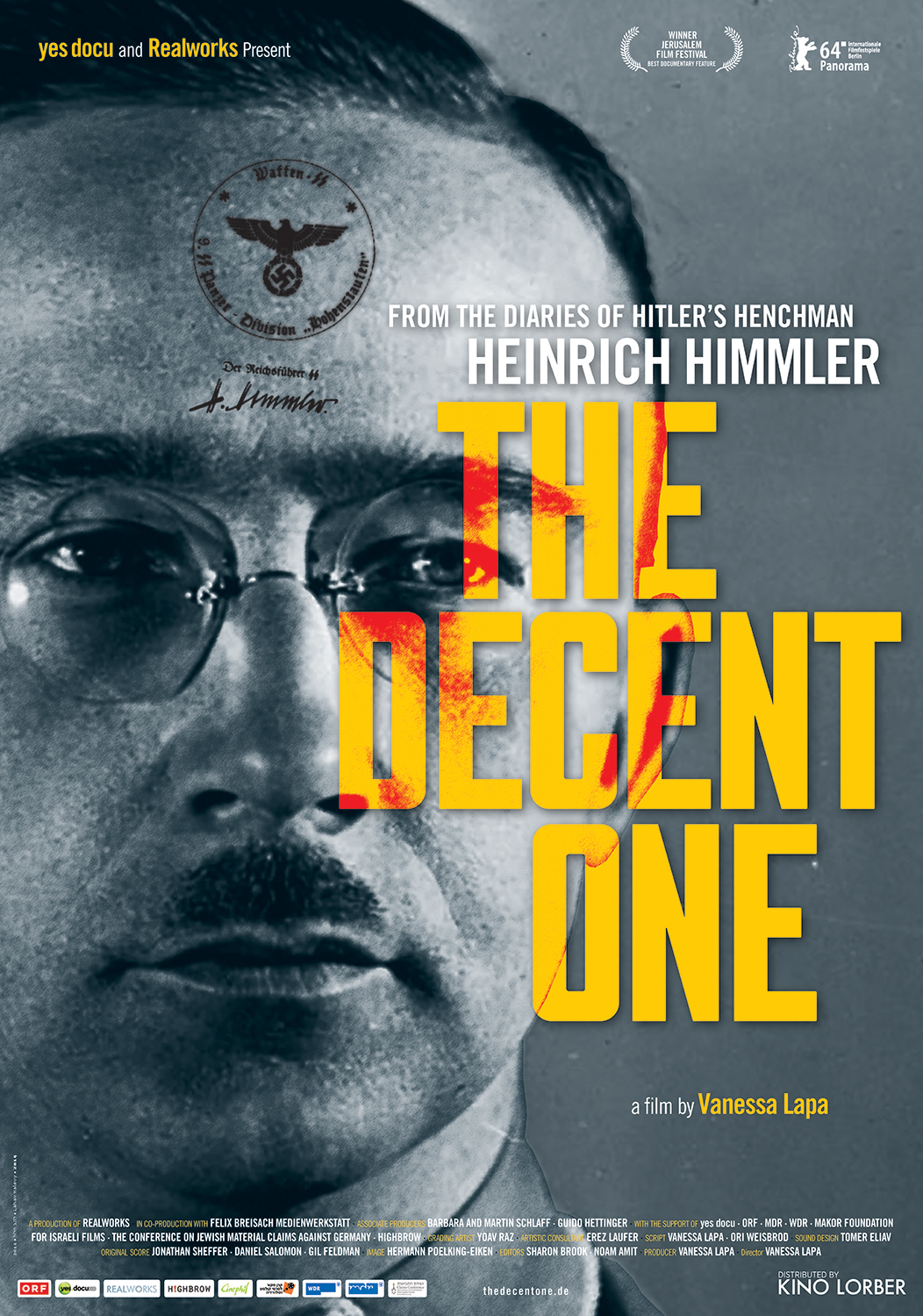

FilmJuice have my review of Vanessa Lapa’s documentary about Heinrich Himmler, The Decent One.

The Decent One draws on some private correspondence that was uncovered in Himmler’s house at the end of the war and sold into private hands by light-fingered American soldiers. Following the scandal surrounding the so-called Hitler diaries, the documents never made that much of a splash and were never made public until Lapa’s parents decided to buy them for her so that she could make a documentary about them. The result is a rather frustrating experience as while the film does give some fascinating glimpses into what life must have been like for the friends and family of prominent Nazis, Lapa chooses to focus most of her attentions on Himmler rather than the people around him.

This evidently put Lapa in something of a sticky situation as how do you produce a biographical documentary about a prominent Nazi without inviting unflattering comparisons to Hannah Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem or more psycho-sociological writing such as Adorno’s The Authoritarian Personality. Lapa tries to overcome this problem by unearthing scandalous biographical details such as Himmler’s penchant for sadomasochistic sex and his habitual drug use but the methods she uses to present these so-called biographical details are so manipulative that you can’t help but raise a sceptical eyebrow:

Lapa makes a great show of putting the documents in the foreground of the film and many shots of Himmler’s angular hand-writing give the impression that the documents are being allowed to speak for themselves. However, take a step back from the images of Himmler’s correspondence and you start to realise that Lapa’s editorialising is so aggressive that it smacks of desperation and frequently borders on the outright manipulative. For example, one of the earliest exchanges of letters between Himmler and his future wife finds Himmler referring to himself as a ‘naughty man’ for spending too much time away from his fiancé, to which the woman playfully responds that she will exact a terrible revenge for his absence. Now… in the context of hundreds of personal letters, this exchange would probably come across as the slightly awkward flirtations of a sexually active couple but Lapa isolates these sentence fragments and instructs her voice actors to deliver readings that encourage the audience to conclude that the future Mr. and Mrs. Himmler has a relationship that was a bit kinky if not actually sadomasochistic. Also suspect is the way that Lapa juxtaposes a document relating to stomach problems caused by prolonged opium use with Himmler’s passing assertion that he had experienced a touch of constipation while on the Eastern front. Again, when seen in the context of an on-going personal correspondence, such an admission might come across as little more than a comment on Himmler’s health but Lapa frames the information in a manner that encourages us to infer that Himmler was a habitual drug user. Aside from being dubious historical practice, such manipulative sensationalism only serves to highlight the extent to which Lapa struggles to find anything new to say about Himmler that hasn’t been said before: There are no private doubts to be found here, only the belief that he was doing the right thing and that history would prove him right.

Surveying some of the film’s other reviews, I notice that I am not the only one to dislike the heavy-handedness of Lapa’s editorialising. Setting aside the fact that films like Shoah set the tone for Holocaust documentaries by allowing people to speak for themselves, I am also struck by the fact that there is now a very fine line between a serious documentary about the Nazis and the type of sensationalist trash you get on cable TV. Massage the primary sources a bit too much and your careful documentary turns into Hitler’s Henchmen by way of Secret Weapons of the Luftwaffe.