The last time I wrote about the films of Apichatpong Weerasethakul, I suggested that his films constituted a challenge to the critic. A reminder, if you will, that as cinematic expression evolves, so too must the tools of the critic. Indeed, most of the critical reaction to the Thai-film-maker’s work has tended to emphasise either the biographical (Weerasethakul is gay and his parents are doctors, facts that have clearly inspired his film-making) or a form of woolly mysticism that attempts to alight upon his films with the same softness and the aloofness that Weerasethakul uses in examining different topics in his films. In other words, Weerasehakul is not a forensic film-maker and so it is okay to speak of his films in non-forensic terms. For my part, the jury is still out on this approach. Especially when you consider that Weerasethakul’s earlier films seem to be quite accessible to standard critical readings.

Indeed, Blissfully Yours (Sud Sanaeha) could easily have been made by a European art house director. It is, after all, a fairly straightforward exploration of the temptation to ignore one’s problems in order to take pleasure in the present. While the film does share many of the images that Weerasethakul would deploy so forcefully in films like Syndromes and a Century and Tropical Malady, it is also a much darker film. A film that seems strangely at odds with the warm-hearted mysticism of Weerasethakul’s later films and the critical reaction to them.

The film opens in a doctor’s office. Being examined on the couch is a handsome young man named Min (Min Oo). He does not speak. He is completely passive. When the doctor asks him questions they are answered instead by a young woman named Roong (Kanokporn Tongaram) and an older woman named Orn (Jenjira Jansuda). However, the passivity does not appear to be a reflection of Min’s medical condition. He has skin lesions and a sore throat that apparently prevents him from speaking but the two women appear to be using the young man as the basis for some scheme. Indeed, Orn repeatedly begs the doctor for a medical certificate for Min but the doctor refuses as she has not seen any identification confirming his identity.

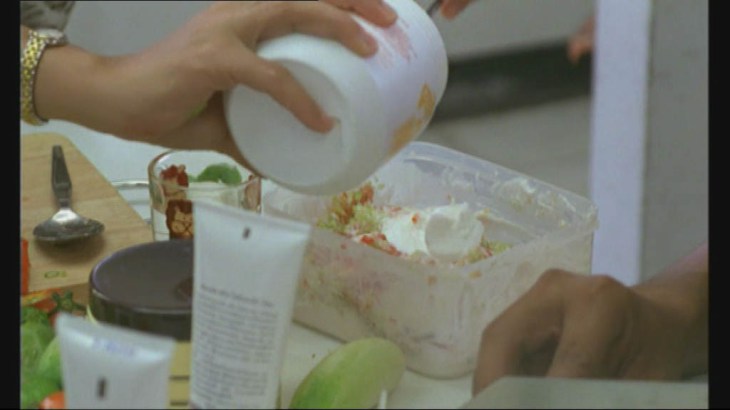

As we move out of the doctor’s office, Weerasethakul fills in the back-story and the network of relationships that animate it. It would appear that Min is an illegal immigrant from Burma. He is dating Roong and Roong is paying Orn to help Min get the paperwork that will allow him to work in Thailand. Paperwork that can be gained using an official medical certificate. Orn is married and desperately wants a child. A child that her husband seems incapable of providing her with. As a result, she has started an affair with a younger man and clearly has eyes for Min. Roong is aware of this and there is a tension between the two women. A tension that is played out comically over a pot of moisturiser. Moisturiser bought at great expense by Roong and ‘improved’ by Orn who dumps a load of fruit into it in order to help Min treat his skin problems. Because of Roong’s possessiveness of Min, she has also taken to leaving work early. This means that she is failing to meet her quotas and she may well lose her job as a result. Weerasethakul establishes all of this baggage with astonishing grace and economy. Within forty minutes, the stage is set for what might be described, in dramatic terms, as a huge barney. But the barney never comes.

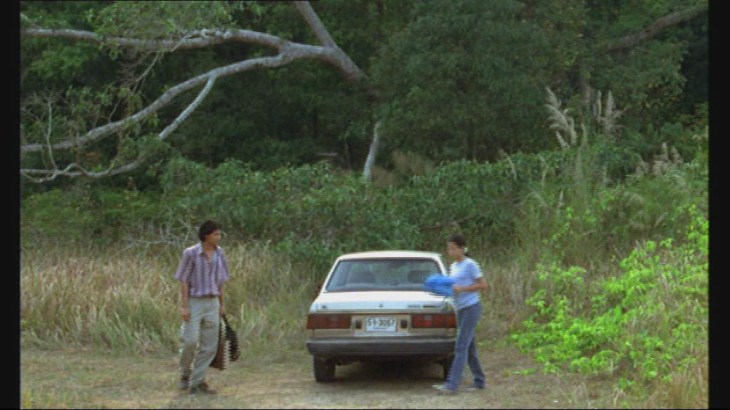

Instead Weerasethakul changes the game. Much like Syndromes and a Century and Tropical Malady, Blissfully Yours is a film in two acts. Acts in which the forest serves as a kind of secondary world. A world in which emotions loom larger and the fantastical becomes a distinct possibility. This is the forest that appears as a backdrop to the first half of Syndromes and a Century but not the second. This is the forest in which a country boy turns into a tiger in Tropical Malady. Weerasethakul’s use of the forest as a visual motif for escape from reality (whether psychological, emotional or fantastical) is reminiscent of Japanese director Hideo Nakata’s use of water in such films as Dark Water (2002) and Ring (1998).

Here, the forest is presented as a venue for escaping from the pressures of the real world. It is a place of emotional stasis. A place where people’s problems might melt away. It is like the Zone in the Strugatsky Brothers’ Roadside Picnic (1972) and Tarkovsky’s Stalker (1979), or the mysterious lunar structure in Budrys’ Rogue Moon (1960), or the Event Site in Harrison’s Nova Swing (2006). A place where cause and effect is somehow disrupted. Except of course it isn’t. Because you can’t escape your problems so easily. Min takes Roong to the forest in order to help her chill out from work (a strange idea in itself as Roong is seldom at work and what work-related problems she does have stem from her tendency to keep taking time off). But Orn is also present in the forest with her husband. The two couples spend their time in the forest in a state of Edenic bliss. Happily wandering through the trees, allowing the water to lap against their feet, having sex and eating.

The desire to avoid the problems of the real world is so intense that the characters become completely passive whilst in the forest. As though they have been infected with whatever it is that affects Min. At one point, Orn wanders away from her husband and finds her way to the younger couple. Along the way she gets lost and stumbles across a load of drums seemingly containing toxic waste. It is as though she somehow has to quest in order to reach Min and Roong.

When she does, her desire for Min is obvious and the tensions between the women begin to resurface but the mood of the forest is such that the two women never quite have an argument. Instead they bathe Min together and then Min and Roong go off and have sex alone while Orn lies on the floor weeping. Weeping for her failure to seduce Min. Weeping for her failures. Weeping for being left alone.

It is telling that Min’s only action in the film is to lure the women to the forest. It is a place in which Min’s apparent passivity comes to infect the people around him. Min’s role in bringing Orn and Roong to the forest underlines the darkness of the character. Min is not simply a sex object, he is an object of addiction. His presence in the lives of both Roong and Orn is unhealthy. It leads to them risking their relationships and their jobs in order to be with him. Min is both a receptacle for Roong and Orn’s refusal to deal with their real-world problems, and a multiplier of those problems. He is an invitation to mortgage one’s future for the pleasures of the present. A fact nicely illustrated by Min’s chance encounter with a man who, within seconds, makes a pass at him. Then, a few minutes later, we see the man on a motorbike pursuing the car containing Min. Min is the promise of the moment. A present moment which, in the forest, seems to last for ever, but which is ultimately only ever going to be short-lived. Min offers the promise of escape but because one cannot so easily escape one’s real world problems, he is a problem in himself. Indeed, Min’s dark nature is further reflected both in Weerasethakul’s comments about the character (namely that he wrote the script thinking that Min had AIDS) and the pre-credit epilogue, in which it is revealed that Min soon moved on to another place leaving Roong to return to her original boyfriend. A boyfriend she returned to, presumably, without a job but with the HIV virus.

Blissfully Yours serves as a fascinating counterpoint to the magical realism of Tropical Malady. It is a much darker film because it shows a strange scepticism regarding the whimsical and fantastical elements that Weerasethakul would go on to introduce into his later films. It is a film that appears to speak directly to the characters of Tropical Malady as though to say “Don’t wait until you’re in the forest. If you love each other do something about it now!”.

Glad to see that someone is paying thoughtful attention to this unique film maker.

I wish that there were more artists like him in Thailand. Most of the other Thai films that I have seen seem highly derivative and/or genre bound.

I’ve seen a few films by Wisit Sasanatieng and Pen-ek Ratanaruang. I would really like to see Thai film making that settles down and takes a look at life as it is lived across the different regions and strata of Thai society. It seems like having gone through the limited catalog of these directors’ films, there is no where else to go. What’s left seem to be action movies, asian horror, overheated melodramas and royalist historical drama.

LikeLike

Hi Paul,

To be honest, I have yet to discover either of the directors you mention. Or if I have their names did not register. So I’m not that well informed on the Thai film scene sadly.

However, I will say that a healthy genre film scene is frequently a proving ground for a generation of directors to come. So I wouldn’t lose hope quite yet :-) Japan and S. Korea have a similar problem but they are still producing decent directors.

LikeLike