The role of a critic is a somewhat paradoxical one. At times of universal agreement over aesthetic principles, the critic serves as a guard dog. A martinet. Forever wielding his rhetorical staff to smack down those who refuse or fail to toe the line. Like Robert McKee we point solemnly to Aristotle’s Poetics and wearily (almost sadly) shake our heads. In order for criticism to escape the quicksands of qualification and relativism, there has to be a belief in universal principles. There have to be rules and there has to be an order to things. But what are these rules? Where do they come from? Are they, like the laws of physics, universal and embedded in the substance of the universe? If our universe contained no sentient life forms, would it still be the case that a character must suffer after a reversal of fortunes in order to realise where he has gone wrong and how to proceed?

I suspect that aesthetic sensibilities are the products of their owner’s culture. The values themselves are formed over time by generation upon generation of artists telling similar kinds of stories and yet gradually changing both the stories and the forms those stories take. This is why older texts can seem odd or unbalanced to modern readers. It is also why critics have to be alive to the possibility that sometimes, a failure to toe the line is not a failure but a great success. As John Crowley puts it in The Solitudes (1987), the first part of his Aegypt cycle :

“It seems to me that what grants meaning in folk tales and legendary narratives – We’re thinking now of something like the Niebelungdenlied or the Morte D’Arthur – is not logical development so much as thematic repetition. The same ideas, or events, or even the same objects recurring in different circumstances. Or different objects contained in similar circumstances. (…) A hero sets out (…) to find a treasure, or to free his beloved, or to capture a castle, or find a garden. Every incident, every adventure that befalls him as he searches, is the treasure or the beloved, the castle or the garden. Repeated in different forms like a set of nesting boxes. Each of them, however, just as large, or no smaller, than all the others. The interpolated stories he is made to listen to only tell him his own story in another form. The pattern continues until a kind of certainty arrises. A satisfaction that the story has been told often enough to seem, at last, to have been really told. Not uncommonly, an old romance’s story just breaks off then, or turns to other matters. Plot, logical development, conclusions prepared for by introductions or inherent in a story’s premises, logical completion as a vehicle of meaning… all that is later. Not necessarily later in time but belonging to a later, more sophisticated, kind of literature. There are some interesting half-way kind of works like The Fairy Queen, which set up for themselves a titanic plot , an almost mathematical symmetry of structure, and never finish it… never need to finish it. Because they are, at heart, works of the older kind. And the pattern has already arisen satisfyingly within them. The flavour is already there. So, is this any help to our thinking? Is meaning in history like the solution to an equation or like a repeated flavour? Is it to be sought for, or tasted?”

This passage raises two interesting ideas. Firstly, it raises the possibility of a time when different aesthetic principles were in force. The Arthurian myths and romances are not primitively written works with a questionable track record when it comes to coherence, but rather works that appealed to a different idea of what makes a good story. Not all stories need to take the same form or follow the same rules in order to be great. Not all conceptions of character have to fit in with our current folk-psychological models. Secondly, it hints at a model of aesthetic revolution. An almost Darwinian process through which stories are told, abandoned, revisited, rebooted, reinterpreted and retold. Crowley is speaking of stories within a certain mythical tradition or saga but might this not also be true of the telling of stories in general? Might this process not also explain how certain kinds of story-telling can evolve over time?

Carlos Reygadas’ Silent Light (2007) has appeared on a number of ‘Best Films of the Decade’ -type lists. I consider it to be quite a dull film. My problem with Reygadas’ work is that it is a film that deals in themes and techniques that will be familiar to anyone who has seen a work of post-War cinema. It clings limpet-like to the existentialist tradition that was pioneered by the likes of Bergman and Antonioni and it explores these well-trodden themes using the same set of cinematic techniques that all art house directors have been using since the 60s. Silent Light contains long takes. Silent Light contains awkward silences. Silent Light contains ambiguous plotting. Silent Light contains a fantastical dream sequence. To watch Silent Light is to gag on the stench of intellectual decay. It is as though the post-War art house consensus has finally played itself out, its stories told and retold using the same old techniques. Just as the Cahiers du Cinema critics who would become the directors of the Nouvelle Vague once rejected the theatricality of French post-War cinema, do we stand at a point in time when the story-tellers have to move on? Must new tools and new stories be told for this and the next generation? One director who seems to instinctively answer this question with a resounding affirmative is Apichatpong Weerasethakul, the Thai director whose Tropical Malady I wrote about a short while ago. His Syndromes and a Century is not merely a good film, it is a film that makes a robustly compelling argument for Weerasethakul to be considered one of the greatest living film-makers.

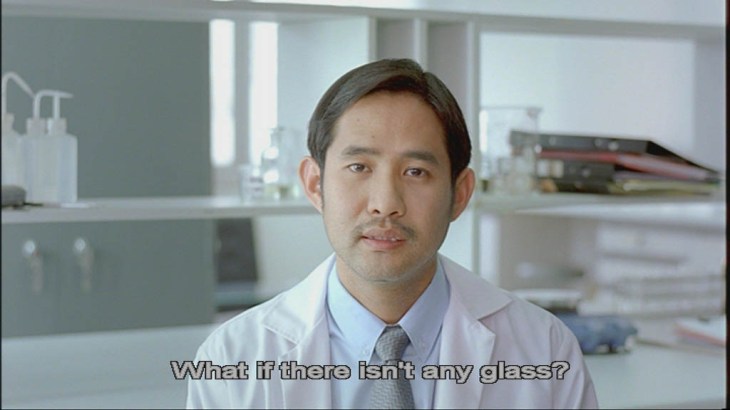

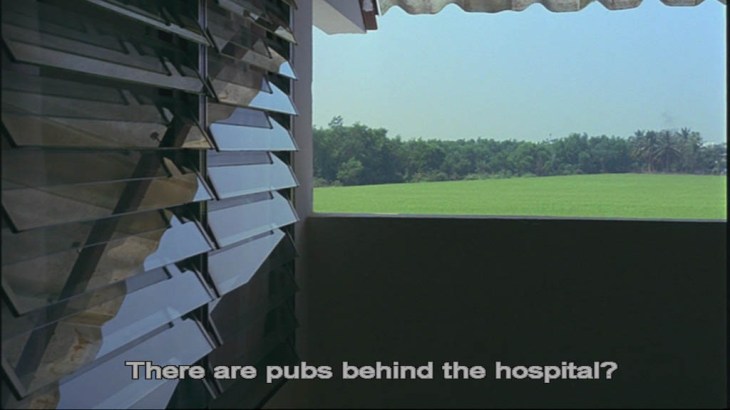

Syndromes and a Century begins in a light-hearted and humanistic vein. The first half of the film is set in a rural medical centre. Out the window we can see trees, the rooms are bathed with warm sunlight. The sense of well-being and relaxed happiness also envelops the patients and doctors who are all merrily eccentric. We are shown a pretty female doctor (Nantarat Sawaddikul) bamboozling a former military doctor (Jaruchai Iamaram) with a series of bizarre interview questions. We see the same female doctor trying to reason with an elderly monk who is plagued by chicken dreams and desperate to trade herbal infusions for sleeping pills. We are then shown one of the elderly monk’s acolytes (Sakda Kaewbuadee) hitting it off with his dentist. Apparently the monk wishes he could have been a DJ. Apparently the dentist is also a successful Thai Country and Western singer. While a lot of the warmth and humanity of the medical centre flows from the look of the place and the way in which Weerasethakul lights it and films it, it also seems like a happy place because it is filled with potential love. The female doctor is clearly flirtatiously teasing her terrified interviewee before fending off the romantic devotion of another hospital employee with a story of her relationship with a local orchid farmer. Even the monk and dentist get in on the act when their discussions take a decidedly romantic turn.

As with Tropical Malady’s cinema sequence, Syndromes and a Century’s moments of romantic tenderness fizz with incredible joy, excitement and sexual tension as the polite formality of Thai small-talk melts almost seamlessly into a seductive and subtle ballet of suggestion, reciprocation and escalation. An impression only heightened by the very unadorned timbre of the sub-titles on the BFI edition of the DVD. Apichatpong Weerasethakul is a genuinely gifted observer of the subtleties of human mating rituals and he reproduces them on-screen with dazzling effect. It is simply impossible not to smile when the dentist asks the monk whether he is the reincarnation of his dead brother.

Then, halfway through the film (as with Tropical Malady), a change takes place. We move from the warmth of the rural medical centre to the cold technology of a huge city hospital. Gone is the warm sunlight, replaced by artificial lighting. Gone are the trees and rivers, replaced by stark angles and concrete. We no longer have whimsical patients but rooms full of amputees learning to walk with artificial limbs. Clearly, the world has moved on. Yet some things have stayed the same.

The film reprises two particular scenes. The now greying former military doctor undertakes the same job interview. His answers are the same but his manner is more confident. When he leaves the room, as in the first version of the scene, the interviewer is approached by someone who gives her a gift. Similarly, we see the old monk. Still plagued by chicken dreams. Still trying to exchange questionable herbal remedies for real medication. This time the monk who is having his teeth examined has a cloth pulled over his eyes. Each time he attempts to remove the cloth, the dentist puts it back in place. A couple make out in the doctor’s office but the kiss seems as cold and loveless as the office building itself. The woman shows the doctor images of a huge building site, she asks him whether he would like to move there in order to be with her. The doctor is silent. There is no friendship or love to be had here.

This motif of repetition and change is an intriguing one that brings to mind Crowley’s words on traditional literary forms. Weerasethakul has said that the film is partly biographical and based on the lives of his parents. This invites an interpretation of hostility to change. As the doctors grow older the world around them becomes harsher and colder and yet the same problems remain. The same people are looking for love, friendship and drugs but not finding them. But this rather literal interpretation of the film ignores the metaphysical character of much of the dialogue. Throughout the film, the characters speak of their former and their future lives. As Buddhists who buy into the idea of reincarnation, this is clearly a pressing concern. When the dentist suggests that the monk may be his reincarnated brother, there is the suggestion of a deep bond. A depth not only between people but also within them. For some of these characters, reincarnation and dharma are central to their worldview, central to the folk psychological models they use to make sense of other people. For Buddhists, lives are lived over and over again with variations and yet the souls remain the same. Forever accumulating and losing spiritual capital as the wheel continues to turn.

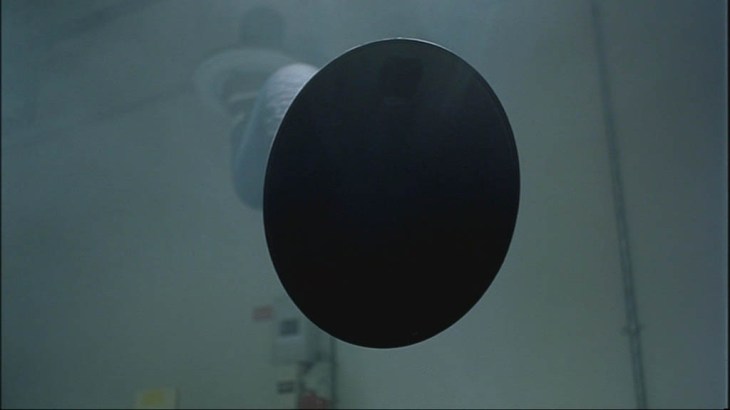

Syndromes and a Century expresses a very particular attitude to change. The film seems to suggest that each moment is filled with possibility. Possibilities of love, possibilities of happiness and possibilities of sadness. Sometimes our lives will go through good patches, filled with positive possibilities, and other times they will go through periods of darkness even though ostensibly nothing very much has changed. The film ends with a wonderfully haunting montage of shots. We see work going on in the hospital, as though time and the passage of a life calls for its dismantling. We see smoke being sucked into a black pipe. We see statues in a park, testaments to former lives. Then we see people walking through the park on a warm-looking evening. The film ends with footage of a huge aerobic routine conducted in the park to an insanely catchy and up-beat pop song. The wheel has turned and we move from an age of technological austerity and aloofness to one that seems filled with more fun and whimsy.

Apichatpong Weerasethakul is a director who works largely through suggestion. His palette is one of moods and ideas that are offered up to the audience not, as Crawley puts it, as an equation to solve, but rather an intellectual dish to be sampled and slowly digested. Compare it with a similar film from the Western art house tradition and this distinction snaps immediately into view. Gus Van Sant’s Elephant (2003), much like Reygadas’ Silent Light, uses a certain number of techniques to explore a certain number of themes familiar to fans of this kind of cinema. Like Weerasethakul he uses repetition of key scenes but these repetitions are attempts to look at a similar phenomenon from different perspectives. We watch Elephant and we slowly pull together not only the time-line of the day of the shooting, but also what might have caused the shooting in the first place. Van Sant drops hints with astonishing skill and grace such as when he undercuts the clean-cut happiness of the Highschool with scenes of bullying and bullemia, suggesting that not all is well. He also has a group of students discussing homosexuality only for the shooters to be seen showering together. These ideas operate not at the level of mood but at the level of the plot device. Elephant is not a film to be sampled, it is a film to be solved.

Rewatching Syndromes and a Century, I am struck by the danger that any serious piece of interpretative writing about it (as I attempted above) might crush the film’s gentle semiotics. To nail down the films of Apichatpong Weerasethakul is to collapse their wave function and to end their gentle interplay of ideas and possibilities. Just as film directors need to develop new ways of telling stories, so critics must attempt to find a way of discussing such experimental works without treating them as works from an older age. This might well go some way to explaining why it is that critics like these kinds of films far more than most cinema goers. To sit before a blank laptop screen with a desire to write about a film such as Syndromes and a Century is an opportunity to break new ground, to be a cartographer, to build a new aesthetic. That is a wonderful challenge for a film-maker to offer.

[…] Syndromes and a Century (2006) [Ruthless Culture] : A great film, though I find it difficult to write about this film maker without dissolving […]

LikeLike

[…] the film does share many of the images that Weerasethakul would deploy so forcefully in films like Syndromes and a Century and Tropical Malady, it is also a much darker film. A film that seems strangely at odds with the […]

LikeLike