I grew up within gobbing distance of the Kings Road and can still remember teenaged punks charging tourists for photos and shitting in doorways opposite what is now an enormous McDonalds. I remember when postcards of London still featured punks and I remember when rising property prices finally rid Chelsea of its art school pretensions and replaced them with the cosmopolitan brutality of a first class airport lounge. I remember the aftermath of the British punk scene but I was too young to appreciate it… all I have to go on is what history has taught me.

Anyone who grew up in Britain during the 1990s will be familiar with the broad narrative beats of British punk history as laid down by the Sex Pistol–Media–Industrial-Complex: From the poorly attended gig at the Manchester Lesser Free Trade Hall to their expletive-laden appearance on the Bill Grundy Show and on to mocking the Queen’s silver jubilee from the top of a chartered boat. We are familiar with these narratives because they are the origin stories of people who would later become very popular and very successful. The truth about the British punk scene might have endured the deliberate revisionism of Julien Temple’s The Great Rock n’ Roll Swindle but it was never going to survive Alan fucking Partridge:

Narratives are easy to steal, history is easy to re-write and the truth will always be closer to the unformed opinions of people who were there than the polished anecdotes of those exact same people twenty years down the line. The truth about British punk may lie buried in interviews and half-forgotten fanzines but part of the truth about one corner of the LA music scene recently returned to DVD in the form of a swanky box set.

***

Comprising interviews and live footage from gigs played by bands such as Fear, the Germs, X, the Circle Jerks and Black Flag Penelope Spheeris’ The Decline of Western Civilization is a fascinating look at a scene that was still in the process of finding an identity.

Nowadays, we would talk about the LA punk scene of the late 1970s as a community but ‘community’ is a word that hides almost as many sins as it does inaccuracies. As the agitprop columnist and vocalist for Catholic Discipline puts it: “There’s no more brotherhood shit… Everybody’s grooving on different vibes”. I prefer thinking of groups as neighbourhoods rather than communities as ‘community’ implies fixed boundaries and enforced togetherness while neighbourhoods are semi-random collections of people who just happen to be responding to the same things at the same time. People move in, people move out, and sometimes togetherness is little more than a nod of the head as you go your separate ways.

Structured around a series of live performances and interviews with the performing bands, the first Decline of Western Civilization film may fail to conjure the spirits of community but it does explore a particular cultural neighbourhood and examines how different people responded to similar energies in a variety of different ways. For example, while Exene Cervenka and John Doe of X come across as art school drop-outs obsessed with trash culture, Darby Crash of the Germs comes across as a self-destructive derelict incapable of stringing together two sentences let alone an entire performance without necking whatever drink and drugs happen to come his way.

The scene’s psychological diversity is also evident within particular bands so Ron Reyes from Black Flag seems like a typical teenage boy who enjoys the attention and cracks jokes about collecting the underwear of his sexual conquests while the band’s bass-player Chuck Dukowski talks about his studies in psycho-biology and makes insightful comments about the nature of the scene and other groups renting space in the abandoned church that the band calls home.

Naturally, the differences between the bands translate into different styles of performance. For example, the only thing distinguishing members of the Germs from members of the audience is the fact that they have instruments but even then, Darby Crash frequently forgets to sing into the mic. Conversely, X come across as well-rehearsed and technically proficient, hence their receiving bouquets of flowers from promoters grateful for any show of professionalism and/or competence. Despite approaching their performances and music in very different ways, all of the bands talk about being banned from various venues and are at pains to point out that while punk rock shows may look like riots, they’re actually just concerts where young people let off steam. The need to balance competence and spontaneity is central to all of the performances included in the film and the best performers are those who manage to channel the audience’s energy in a deliberate fashion. For example, the band Fear make repeated references to being from ‘Frisco’ in order to get on the LA crowd’s bad side and then lambast them with homophobic taunts before claiming to be gay themselves. They then throw change at the audience in a ridiculously insulting effort to placate them and launch into a song just before the crowd decides to rush the stage. Anger is the energy that fuels punk rock… but that energy is harnessed in many different ways even within the same scene.

As a side note, Fear are quite a significant act as their performances in The Decline of Western Civilization prompted John Bellushi to invite them onto Saturday Night Live. Once on stage, the band talked about how nice it was to be in New Jersey and harangued the crowd until the performance spiralled completely out of control. The resulting footage includes a very young Ian McKaye of Minor Threat and Fugazi shouting “New York Suuuucks!” at the 4 minute 17 seconds mark:

One of the most interesting things about this film is that all attempts to understand the essence of punk or articulate a shared mission for the scene seem to come not from the bands but from the people trying to make money from their shows. Venue owners, managers and promoters are quick to talk about protest-style lyrics and music played too fast for dancing but the bands seem content to talk about their experiences. In fact, while the bands recognise the importance of the venues, they are very reluctant to acknowledge anyone else’s existence. This could be a reflection of the fact that they are all ‘grooving on different vibes’ but it could also suggest that aesthetic convergence was a function of economic reality rather than shared sensibility. Without venues looking for bands that could play fast, angry music for mosh pits full of fucked-up teenagers, would any of these bands have wound up sounding even remotely similar? It’s an interesting question that goes some way to explaining why the scene captured in this film feels so vibrant: The bands in The Decline of Western Civilization are mostly interested in doing their own thing, they have not yet fallen into the trap of performing either their ‘punkishness’ or ‘LA punkishness’. They are raw, unformed and free.

***

The first Decline of Western Civilization film was an unexpected success. When producers booked a 1,200-seater cinema for the documentary’s late-night premier, the local music scene turned out in such huge numbers that 300 police were called in to keep order. LA Police Chief Daryl Gates would later write a letter to director Penelope Spheeris demanding that she never show the film in LA again. The documentary’s unexpected success also did wonders for Spheeris’ career as her ability to capture the bleeding edge of the LA music scene opened doors leading to jobs directing gritty LA films about gritty LA people.

As Spheeris built her career, the LA music scene changed. Fed up of near-riots and playing to kids without money, the clubs of LA’s sunset strip continued banning ‘unprofessional’ punk bands as radio stations replaced the queer-friendly multiculturalism of disco with the white-bread machismo of the few stadium-filling rock bands that had managed to survive the 1970s. Hungry to experience live music but alienated from the emotional chaos and art school sophistication of the local punk scene, LA teenagers began throwing their weight behind bands inspired by the adolescent hedonism of what was rapidly turning into a multi-million dollar transatlantic industry.

The major difference between the first two films in the Decline of Western Civilization series is that while the first film is all about the authenticity of the LA punk scene, Part II is all about inauthenticity and how a vibrant youth culture was replaced by a culture in which teenagers try to turn themselves into sellable properties by assuming personas created by people old enough to be their parents. This means that while Part I of The Decline of Western Civilization is earnest and inspirational, Part II is both funny and depressing. Little wonder that Spheeris progressed from making this documentary to directing Wayne’s World.

The Decline of Western Civilization Part II: The Metal Years is structured as an oblique dialogue between members of established metal bands and much younger LA teenagers desperate to follow in their footsteps. The documentary begins by giving older musicians enough rope with which to hang themselves, and so we have Kiss’s bass-player Gene Simmons being interviewed in a lingerie store like the leader of the parliamentary Sleaze party while the band’s vocalist Paul Stanley is interviewed in bed surrounded by groupies. Pushing 40 and already multi-millionaires, the two men pay well-rehearsed lip-service to the libertarian fantasies of commercial rock and roll while Spheeris’ careful staging draws our attention to the vacuity of their words.

Films like Wayne’s World and Airheads may well have convinced the world that metal is one enormous case of arrested development but that critical analysis began with Rob Reiner’s This is Spinal Tap and expanded when Spheeris drew people’s attention to the fact that 80s metal was dominated by men in their 40s pretending to be teenagers and making fortunes in the process.

While the LA punk scene of the early 80s was a product of musicians and promoters working together to create something coherent, the late 80s saw the power balance tip in favour of promoters. This meant that the thinkers and evangelists of Part I were replaced by a group of much older and more exploitative club owners who encouraged bands to play on their sexuality as a means of attracting young women who would then be encouraged to dress provocatively as a means of attracting teenage boys. Spheeris is particularly impressive when analysing the scene’s complex gender politics as she speaks to a number of teenage boys who talk about the transgressive joys of wearing make-up and long hair only for the band Poison to talk about how female fans love guys in make-up. This cynicism is then brutally unpacked using images of a ‘rock and roll dance competition’ where teenage girls perform strip-teases on stage in front of male audiences and juries comprising nothing but ageing male rock stars.

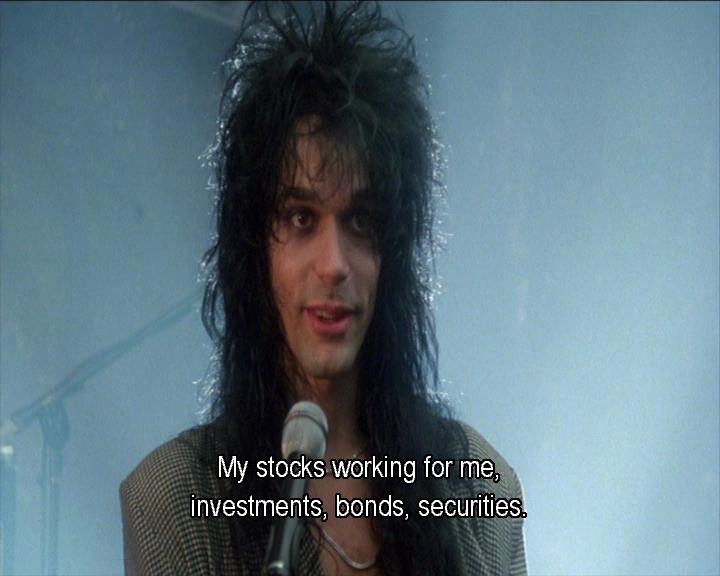

By far the most interesting thing about the cynicism of the metal scene is the way that it seems to have been internalised by audiences. For example, while the bands in Part I show little interest in either money or stardom, all of the bands interviewed in Part II talk about money and the need to treat the scene as a career-building opportunity. The real intellectual schism at the heart of the 1980s metal scene appears to have been between those people who believed that metal really was about hedonism and those who realised that it was all about the appropriation and exploitation of adolescent sexual fantasies.

As the film draws to a close, Spheeris shifts her attention away from cynical acts like Kiss and towards more self-aware musicians like Ozzy Osbourne. Osbourne is a fascinating figure as while he was one of the first musicians to deploy the satanic tropes that would later become tiresomely ubiquitous in the world of metal, he has always been able to step back from his stage persona and talk about his own vulnerability and incompetence. Spheeris films Osbourne trying to make breakfast and there’s a lovely moment where he tries to pour orange juice into a glass only for his perpetually-shaking hand to send it spraying across the entire table. Though reportedly faked, this footage is perfectly in keeping with Ozzy’s message that metal is an industry that has turned many of its most successful performers into drunks, drug-addicts and emotionally-crippled burn outs.

Though undoubtedly funny, The Decline of Western Civilization Part II is extraordinarily depressing in that Spheeris exposes not only the cynicism and intellectual vacuity of the scene but also the creative bankruptcy of the music itself. Unlike Part I, where all of the bands seemed to be developing entirely unique sounds, the bands in Part II look and sound exactly alike right down to the much-discussed and respected decision to start tying scarves to microphone stands in order to have a bit more visual impact whilst crooning and/or rocking out. Spheeris is brutal when exposing the scene’s lack of creativity as one of the performances she chooses to include is of a band performing a cover version of Steppenwolf’s “Born to be Wild”, a song first released more than twenty years before the concert was filmed.

Despite being quite scathing about the state of the LA rock scene in the late 80s, Spheeris treats the teenage fans she interviews with the utmost respect. While some seem happy to mouth the usual rock and roll platitudes, Spheeris’ interviewing rapidly unearths traces of sadness and desperation in their pursuit of hedonistic lifestyles. As in the early 80s, many of these kids come from broken homes and spend their days either in abject poverty or working soulless jobs just to make rent. The big difference between the punks of the early 80s and the headbangers of the late 80s is that while the punk kids used music to vocalise their rage and explore their sense of alienation, metal kids used music as an escape and felt forced to justify their escapism in economic terms. Sure they were rebelling… but rebellion can be a great way to kick start your career and become an entrepreneur! Spheeris never directly addresses the cultural shift underlying these changes but it does seem relevant to the fact that contemporary counter-cultures are far more comfortable with careerism, self-promotion and economic exploitation than those of previous generations. The punk kids grew up in the 1970s but the kids interviewed in Part II all reached their teens in the mid-80s begging the question as to whether the real difference between early-80s punk and late-80s metal might not actually be the rhetoric of neoliberalism unleashed by Thatcher and Reagan in the early years of that decade.

It is interesting to note that while the vogue for big-haired metal did not survive the 1980s, metal did return to commercial success in the late 1990s when a number of bands from southern California combined the heavy guitar-based sounds of 80s metal with the vocal styles and performative masculinities of West Coast hip hop to produce a nu-metal scene that would ultimately wind up being dominated by a fresh generation of 30-something men pretending to be teenagers. Desperate not to repeat themselves, these new rock stars eschewed long-hair and songs about chicks in favour of spangled tracksuits and songs that dripped with sophomoric man-pain. Ever the pragmatist, Ozzy Osbourne promptly associated himself with the new trend and his wife-cum-manager used her industry expertise to shift the focus away from reasonably-priced local clubs and towards stadium-filling national tours that ruthlessly syphoned money from teenage pockets until Limp Bizkit’s Fred Durst joined the band Staind on stage and sang about being ugly on the inside, at which point the penny finally dropped and teenagers everywhere realised that these people were just taking the piss.

Since then, metal has re-invented itself as an aggressively inaccessible galaxy of sub-genres where different styles of music meet, mingle, and depart amidst technical brilliance, heavy sounds and dark imagery. Just as weird, primal and anti-commercial as the punk bands explored in Part I of this series, metal’s introverted configuration is weirdly pre-empted when Spheeris interviews Megadeth’s Dave Mustane and finds him critical of music industry cynicism and more interested in exploring his own sound than peddling adolescent fantasies.

***

If Part I of The Decline of Western Civilization gave Spheeris the chance to direct edgy thrillers and personal projects about people living on the fringes of LA, Part II established her as a reliable director of studio comedies. Soul-sucking though this might have been for a woman who obviously felt very close to teenagers lost amidst the nightclubs of Hollywood, Spheeris’ success did allow her to finance Part III of this series and make the film without any external interference. The result is arguably the most insightful and moving documentary in the series and the only film to really merit a titular reference to the collapse of Western civilisation.

We encounter the LA punk scene looking little different to the way it did for the filming of Part I: Bands are still channelling aggression and kids are still feeding on that anger and moshing in dingy little rock clubs. In fact, were it not for the existence of Part II, you could easily be forgiven for assuming that LA became a punk rock town in the late 70s and simply stayed that way for the next twenty years. The pluralism of styles and energies is gone and replaced by a noticeably narrower aesthetic informed by the British punk scene but with a sound that is considerably angrier.

The first major difference between parts I and III are that the punk scene depicted in Part III seems more diverse and politically aware. The lead singer of the band Litmus Test gets the entire crowd to chant “Queer Thoughts!” while Kirsten Patches from the band Naked Aggression delivers on-stage rants about a woman’s right to choose and talks about having played fund-raising gigs for women’s shelters and other deserving causes. The kids themselves are also incredibly passionate about their politics and early interviews mention frequent fights not only with white supremacist skinheads but also with anti-racist skinhead bands that treat the local scene as a recruitment centre for what sound suspiciously like gangs and personality cults.

As in the rest of the series, Spheeris moves between concert footage, interviews with bands and interviews with fans but unlike Part II where the fans come across as victims or Part I where the fans seem to be using the scene to express an anger they cannot yet articulate, Part III makes the fans seem far more switched-on than the bands they listen to as the concerns informing the various’ bands lyrics seem a good deal more generic and abstract than those raised by kids in interviews. The kids aren’t worried about the evils of fascism or organised religion… they’re worried about whether or not they’re going to find somewhere to sleep and whether they’re going to get stabbed by skinheads. In truth, The Decline of Western Civilization Part III is not so much about the LA music scene as it is about kids living in LA and scavenging identities from punk-rock imagery because those were the only identities available to them at the time.

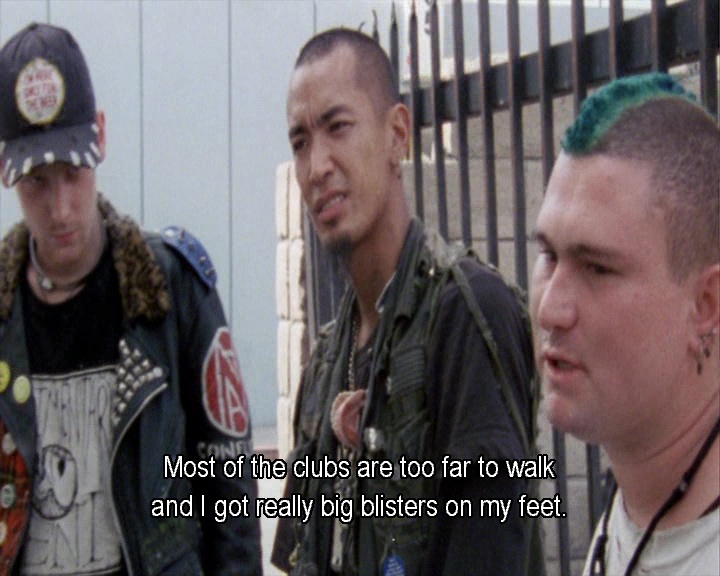

The second major difference between Parts I and III is that while many of the kids and musicians interviewed in Part I had some hope of maybe supporting themselves either through music or by getting a job, all of the kids in Part III are teenage drunks who sleep on the street and support themselves through a combination of pan-handling, theft and sex work. Utterly charming and amazingly articulate, the kids are all products of broken homes and a system that has long-since given up pretending to give a shit about the poor and vulnerable. Spheeris repeatedly asks the kids about going to punk shows but the shuffling feet and embarrassed laughs suggest that these kids would rather spend their money on getting fucked up than going to shows.

The problem with punk is the same problem facing all organised counter-cultures: Scenes may claim to be about freedom and self-expression but in reality they are about the creation of commercially-exploitable spaces in which people can safely perform certain non-conventional identities. As Jello Biafra famously put it “Harder-core-than-thou for a year or two and then it’s time to get a real job”. In this respect, punk rock shows are no different to conventions where people go to ‘geek out’ and express their individuality using intellectual property owned by multinational corporations. We would like to believe that subjectivity precedes exploitation and that the bands, clubs and T-shirts are just expressions of that original subjectivity but the truth is a lot more complex and depressing. The interesting thing about the kids in this documentary is that while they certainly their punk-rock identities in ways that simply would not have occurred to kids in the late 1970s, the precariousness of their position means that the clubs, T-shirts and CDs are completely out of reach.

Given that none of these kids can afford to be part of a music scene and many of them talk about having left home at the age of twelve, the interesting question is why so many of them seemed to have opted for punk-inspired identities. While the film does not really address the question, one answer would be that it is safer to be a punk-rock kid than it is to be a homeless teenager.

The impression I got watching The Decline of Western Civilization Part III is that the kids in the film scavenged their identities from the ruins of the scene that was immortalised and popularised in Part I. One of the nice things about punk is that the barrier to entry is amazingly low: You don’t need much beyond a bit of anger, a second-hand t-shirt and the willingness to do something weird to your face or hair. In fact, this barrier to entry is so low that even homeless teenagers can clear it and clearing it means that they move from being ‘the homeless teenagers sleeping in that burned-out building’ to ‘the punker kids who live in that squat’. Punk might never have been as commercially viable as either rap or metal but it is a universally-recognised identity and there will always be safety in recognition as it provides stock answers to questions that other people might ask of you. Why are you living in a squat? What are you drunk all the time? Why do you spend your days hassling tourists? Why do you smell and wear rags? Well… one answer is that you’re a homeless derelict but another is that you’re PUNK RAWK!

Looking back over the three films, we see the LA rock scene rise and fall like any other civilisation: First we have the emergence of a new subjectivity, then that subjectivity changes in an effort to remain viable but the changes result only in decadence and collapse until someone comes along and tries to reclaim the original subjectivity as part of some semi-mythical golden age which is then used to generate historical gravitas that legitimises actions and institutions with no real connection to the original subjectivity.

The kids in The Decline of Western Civilization: Part III are not the second-coming of the LA punk scene, they are more like people of the Renaissance looking to the Classical period as a means of legitimising a new form of culture that severed the traditional ties with Holy Mother Church. Like characters in some post-apocalyptic science-fiction series, the kids of The Decline of Western Civilization: Part III are picking over the remnants of a once-vibrant cultural scene and using the scavenged legitimacy to justify lifestyles as self-destructive as they are tragic and desperate.

Mark Fischer’s fantastic book Capitalist Realism suggests that we live in an age where Capitalism and post-modernism work to impede the creation of fresh subjectivities. As Fredric Jameson puts it in the essay “Postmodernism and Human Society”:

In a world in which stylistic innovation is no longer possible, all that is left is to imitate dead styles, to speak through the masks and with the voices of the styles in the imaginary museum. But this means that contemporary or postmodernist art is going to be about art in a new kind of way; even more, it means that one of its essential messages will involve the necessary failure of art and the aesthetic, the failure of the new, the imprisonment of the past.

The kids interviewed in The Decline of Western Civilization are nothing less than poster-children for life under neoliberalism, an age where art emerges only to be disrupted and commodified by the perceived need to turn a profit and build careers. Dragooned into museums and taught to speak using only the voices of the dead, people lost the power to speak solely for themselves. Like early humans who hoped to lure the elk and buffalo they saw painted on the walls of their caves, we give ourselves over to ancestor worship. Hopelessly confused as to cause and effect, we adopt the language, beliefs, and dress-codes of our chosen ancestors and hope that staging an effect will somehow resurrect a cause by bringing forth the acceptance and recognition that our ancestors once breathed without thinking.

While gutter punks dressing and behaving like the kids who used to hang out on the King’s Road in the 1970s may be an extreme case of ancestor worship, their instincts are the foundation of the modern age.

Heh, in what’s probably an irony spectacular, I saw The Knitters (the bluegrass band X sometimes tours as) close out a show with a rip-roaring cover of “Born To Be Wild” sometime last decade…

LikeLike

That is quite funny :-)

LikeLike

I was pleased to see this write-up appear in my RSS reader! The first two are spectacular pieces of film (I’ve never seen the third). Part one is a weird document of a culture I claimed as my own as a teenager (and have never looked back); for all its ugliness there’s something beautiful about outcasts, misfits and dropouts coming together to create… something.

Part two, on the other hand, is largely quite vile. I’m glad you teased out the sympathy Spheeris has for the fans who’ve fallen for the myths and dreams of the hair metal era.

Have you read American Hardcore? Fascinating read, drawn together as it is from hundreds of anecdotal accounts from the time, and looking back. There’s a film, too, but while it’s interesting it’s not as raw and honest, or anywhere near as comprehensive geographically.

If you’ve not already seen it I’d also recommend BYO: the Story of Youth Brigade, a documentary and (admittedly somewhat slight) accompanying book. Although the focus is on Youth Brigade, the brothers who formed that band and their label, it’s a really wonderful retrospective on some of the most optimistic, generous, DIY achievements of 80s hardcore punk, from BYO buying and operating its own all-punk venue (pretty much unheard of), to the archetypal ‘punk house’ they shared, to their (very loving and supporting) mom helping stuff vinyl into jiffy bags to ship around the country. I also had no idea, until I watched this, that several of the guys out of Youth Brigade plus a few friends were at least partially, possibly wholly, responsible for 90s swing revival. ;)

LikeLike

I think the mistake Spheeris makes is to enforce a quite hard line between fan and musician.

She rows back from it a bit in Part II where you have kids at one end of the spectrum and Kiss at the other and everyone else somewhere in between. I think that flaw in her approach to the scene accounts for the vileness of Part II where it feels like nothing but an orgy of exploitation.

Part III (which is definitely worth tracking down) maintains that dichotomy but introduces a kind of punk underclass made up of kids who can afford to charge their hair but not to attend gigs (or indeed make rent).

I haven’t encountered either of those works but will definitely track them down. Seems to me like BYO definitely has a better handle on the phenomenon of scene-makers… the people who put loads of work in making a scene come to life before the psychopaths drop in and start monetising the whole affair. I remember going to gigs as part of my local scene and you would see the members of other bands because they understood the need to support, encourage and grow the scene even if you don’t necessarily make any money from it. Totally not surprised to know that the Swing Revival was engineered by punks as it had all the hallmarks of the DIY ethos, it just started shitting money way too early for anything good to come of it :-)

I’m totally with you on the beauty of fuck-ups, outsiders and drop-outs coming together to produce something beautiful. I’m very cynical of ‘scenes’ these days as I’ve seen so many of them turn ugly but the DIY punk scene remains my idea of what creative togetherness is supposed to be about.

LikeLike