Back in 2006 an odd little programme snuck out on BBC Four. The programme was called A Pervert’s Guide to Cinema and it featured nothing but the hirsute and lisping Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek talking animatedly about his favourite films. The director Sophie Fiennes did not impose any limitations upon Žižek’s ramblings: She did not ask him questions. She did not impose themes. She did not even demand that the films Žižek dealt with be ordered chronologically or in any kind of order that might render his analyses more accessible to a lay audience. She simply let him get on with it. Her sole input seemingly being at the level of mis-en-scene, ensuring that when Žižek spoke of Hitchcock’s The Birds (1963) he did so sitting in a motorboat crossing a harbour, or that when he spoke of Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation (1974), he did so from the bathroom and balcony of the same hotel that appeared in the film.

In the four years since A Pervert’s Guide To Cinema first aired, it has come to be seen not as a documentary about film or a series of cleverly shot televised lectures and more as an experiment in documentary film-making. The experiment involved making a documentary about the arts without seeking to explain either the act of creation or the fruit of that process. By allowing Žižek to chat about his favourite films Fiennes was distancing herself from the obsession with biography and context that dominates cinematic depiction of the arts. A Pervert’s Guide to Cinema was not a film about Žižek or a film about films, instead it was a cinematic appercu of the act of artistic creation itself.

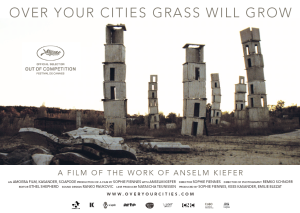

Over Your Cities Grass Will Grow sees Fiennes return to the same philosophical template by providing us with a glimpse into the creative processes of the German installation artist Anselm Kiefer. Over Your Cities Grass Will Grow is not so much an arts documentary as it is an invitation to worship at the unholy altar of an insane god.

In 1992, Anselm Kiefer took over a disused silk factory in the departement of Barjac in Southern France. Over a period of nearly ten years, Kiefer transformed the industrial ruins first into a gigantic studio space and then into a living and breathing work of art in its own right. An immense installation known as a Gesamtkunstwerk. This installation comprises an underground maze, an amphitheatre, vast paintings and a series of towers. The Gesamtkunstwerk fuses the logos of industrialisation with the mythos of Biblical and Jewish imagery to create what can be interpreted as a commentary upon the Holocaust. However, anything as crude as an interpretation sits uncomfortably on the images that Fiennes provides us with, particularly in the hauntingly scored and exquisitely shot wordless walking tour sequences that bookend the film. These are not images that are supposed to make sense to us, they are simply there. The act of interpretation is a vulgar after-thought. An unwanted interloper. A pathetic scrabbling for truth against the sheer scale and weirdness of Kiefer’s vision. A scale so pulverisingly huge that it may as well take in the entire universe.

The unwanted nature of interpretation is beautifully established in a scene in which Kiefer is interviewed by a German art critic. The critic, clearly intimidated, offers up a series of hypotheses as to what Kiefer’s art may be about only for Kiefer to respond with a series of bizarre and rambling tirades seemingly designed not only to put the critic in his place but also to render his own artistic output as terrifyingly inaccessible as possible. When confronted with a fact, Kiefer simply denies it. When confronted with a precise idea, Kiefer expertly evades it. When confronted by a woolly conjecture, Kiefer twists it into incoherent pseudo-philosophical nonsense. The installation is not there to be decoded, it is there to be experienced and this is what Fiennes allows us to do.

By refusing to provide us with any context or critical insights, Fiennes effectively cloaks Kiefer’s creative processes in a compelling aura of mystery. At one point we see him breaking glass and carefully selecting a shard of glass to place in the pocket of a child’s dress that he has glued to a massive canvas and daubed with kabbalistic symbols. At another point we see him mocking up a model of the vast towers he assembles at the end of the film and his selection of materials and shapes seems to be guided by no comprehensible mechanism. There is no message here. There is no aesthetic formula. There is only creation.

Were one to happen upon the now abandoned studio in Barjac one might be tempted to assume that all of these acts of creation were somehow the result of entropy or random vandalism. The towers would be nothing but the bones of some once larger construction. The amphitheatre the remnants of a testing laboratory and the paintings and sculptures a hybrid of decaying corporate art and objects stacked for transport and then left to rust. Indeed, Barjac gives off the same vibe of second-hand humanity as many of the photos from Urban Exploration websites : All of these objects once meant something and served a purpose but now they are just disconcerting and puzzling junk.

To watch Over Your Cities Grass Will Grow is to be thrown into the mindset of a pre-scientific thinker. We look at Barjac and while we can detect some agency at work in the chaos of tortured semiotics, we can only speculate as to what the motivation of that agent might have been. Fiennes casts Kiefer as the psychotic sibling to the tyrant of the Old Testament — an utterly inscrutable creature of immense creative power who remains utterly unaccountable to the minds of mortals. One cannot understand. One cannot explain. One can only experience.

Well, you’ve sold me. This is right up my strasse – ruins, reflection, ambient music, pure imagery. Yep, I’m in.

I am also keen to revisit the Pervert’s Guide To Cinema now too, despite finding Zizek a rather absurd character that I’m constantly amazed gets taken as seriously as he does by the Left. He strikes me as exactly how I’d imagine a cartoon spoof of a Left-Wing Philosopher to be, and seems to come a cropper with his thinking whenever someone makes recourse to, I don’t know, facts or research-based information.

In fact, there’s a whole group of Philosophers – of which Zizek is simply the latest – that seem to have nurtured cult followings due to their outsider status and subsequent approval from Hipsters, as opposed to anything that concrete or revelatory regarding their actual Philosophical ideas (Baudrillard, Deleuze, Virillo would be the other prime suspects). Watching Zizek on the BBC’s Hardtalk, he was visibly out of his depth as soon as rational thought was brought to bare upon his statements to the point where he became quite irritating. In fact, I think it’s this sort of ranting character that limits Left-Wing thinking, rather like Labor clinging to Michael Foot in the 80’s – or even Derek Hatton. We keep reading critics such as Zizek slagging recent (supposedly neo-liberal) policies in response to the Credit Crunch and subsequent economic recession as flawed – which they often are – but nobody ever provides an alternative solution that has any merit or stamina. They simply identify problems. Well, we can all do that, especially with the benefit of hindsight.

As such, I think I’d rather watch Zizek muse about cinema than economics.

LikeLike

Oh yeah… DEFINITELY up your street :-)

Regarding Zizek and their ilk there’s an interesting podcast I listened to recently. It’s part of Entitled Opinions. In this podcast Robert Harrison tries to take on Richard Rorty and challenge him over his tendency to lean to the right and accept the talking points of the War on Terror.

It is hilarious as Rorty effectively bats this bloke about without breaking a sweat. Harrison is a named professor of Italian literature at the University of Stanford.

Similarly, in another podcast, Harrison tries to debate an old friend about the historical Jesus and the interview effectively turns into this brutal deconstruction of Harrison’s analytical capacities as he winds up basically preaching from emotion that there MUST be some truth in Catholicism despite the fact that he does not believe in it.

However, Harrison is an interesting thinker. He’s just a shit analyst.

I think that Zizek is similar (a view buttressed by his very mundane piece on China in the LRB and his piece on Avatar a while back for Cahiers).

These are not analysts, they are effectively conceptual architects whose job it is to use language and concepts to create beautiful ideas. Ideas based upon existing works, events and phenomena.

To look for truth or even insight in such writings is to be naive. That’s not what they’re about. They’re effectively like Catholic theologians… they produce beautiful ideas that we can wrap around ourselves. If they were interested in truth, they’d be scientists.

Zizek is entertaining on cinema because he can take quite opaque films (particularly those of Lynch) and weave these beautiful critical tapestries around them that make sense of images that really make no sense. Zizek on Lynch is like Catholicism on the universe : A pretty picture projected onto a void of meaning.

While I think that this type of thing is fine with regards to the arts (it’s what I do on this blog after all) I think that it is pointless with regards to politics. In fact, it is worse than pointless… it is actively palliative.

LikeLike

[…] Over Your Cities Grass Will Grow (2010) [Ruthless Culture] : Beautiful stuff. Exquisitely filmed piece about a German artist that effectively allows the […]

LikeLike