It was never going to be easy for Claude Chabrol to move on from his most productive period. Between the late 1960s and the early 1970s, Chabrol produced a series of films that would not only secure his reputation to the present day, but also leave an indelible mark upon what comes to mind when one thinks of French cinema. Les Biches (1968), La Femme Infidele (1969), Que La Bete Meure (1969), Le Boucher (1970), Juste Avant La Nuit (1971) and Les Noces Rouges (1973) were shot almost on top of each other with a similar cast of actors who almost came to resemble a repertory company performing only the works of Claude Chabrol. A company of actors who knew exactly what was expected of them in a series of films that positively simmered with anger and resentment at the provincial bourgeoisie who ran the country and defended the status quo while angry young men such as Chabrol climbed the barricades in the hope of creating a better world.

However, watching the films of this period, it strikes me that Chabrol and revolutionary politics were never going to be a perfect fit. Chabrol’s vision of the world is deeply morally complex. When he looks out the window he sees shades of grey rather than the stark black and white demanded by revolutionaries willing to use force to change the world. In fact, while films such as La Femme Infidele, Que La Bete Meure and Les Noces Rouges did a brilliant job of critiquing the middle classes by suggesting a world of sex, passion, drink and self-destruction beneath the mannered politeness and brass-buttons, these criticisms also humanised them. There is something almost comical and easy to empathise with about the husband in La Femme Infidele who kills his wife’s lover but never mentions it to her or the man in Que La Bete Meure who tracks down his son’s killer only to discover that the man’s entire family are hoping that someone will kill him for them. These are not the kinds of people you simply put up against a wall… these are weak, pitiful and ultimately on some level sympathetic creatures. They are victims of the system just like everyone else. Given the general timbre of Chabrol’s work during the late 60s and early 70s, Chabrol’s political history and the political climate of the French cinema scene at the time (Cahiers du Cinema was run by a Maoist collective during the mid-70s) it was clear that something had to give and the result was Nada, a satirical comedy-thriller based upon a noir novel by the influential French writer Jean-Patrick Manchette, that sees Chabrol turning his ire from the bourgeoisie to the functionaries of the state and the radical Leftists who would overthrow them.

Film Poster

Nada is a film that can be seen as part of a tradition of critical works about revolutionary groups stretching back through Jean-Luc Godard’s La Chinoise (1967) to Fyodor Doestoevsky’s Demons (1871) and Albert Camus’ existentialist dramatisation of the novel in 1959. The original plot of Demons featured a group of anti-Tsarist revolutionaries who come together to form a cell only for the cell to implode long before they get anywhere close to threatening the status quo. Doestoevsky portrayed the beliefs of the characters as demonic and dangerous, but suggested that the Russian state was poorly equipped for dealing with them. Camus’ dramatisation was more directly critical, tapping into the idea that if life is absurd then it does not matter which ideology dominates the state while Godard’s near parody presented the characters as romantic and sympathetic soap boxes for the director’s ideals but also bourgeois and faintly comical. Chabrol’s Nada is itself almost a parody of La Chinoise. Instead of presenting us with characters embodying different forms of revolutionary politics, it presents us with characters embodying different forms of disaffection from the cause of the revolution.

For example :

Hat, Coat, Scarf on a sunny day

Padding the Crotch of the Revolution with the Blood of the Workers

Buenaventura Diaz (Fabio Testi) is the handsome poser. Even on warm days he makes sure to leave the house dressed all in black and wearing a wide-brimmed hat, a long black scarf and a long leather coat. His trousers are ball-crushingly tight trousers and makes sure to pad the crotch with a wodge of cash.

Epaulard knocking one back

André Épaulard (Maurice Garrel) is the marginal turned criminal. No longer believing in the cause, he now makes his money as a con man, posing as a lawyer and selling the fictitious whereabouts of Algerian revolutionary war coffers.

The True Voice of the Revolution?

Marcel Treuffais (Michel Duchaussoy) is the jaded intellectual. Once a fire-brand now a drunken high school teacher he prefers talk to action and has started to harbour shockingly liberal doubts about the effectiveness of political violence.

D'Arey making a point which is, I'm sure, entirely reasonable

D’Arey (Lou Castel) is the hot-headed bully-boy turned drunk. During the heist he crows about the fact that he has killed a policeman and vows to drink himself into unconsciousness. He later stands up, stinking drunk, and shouts revolutionary slogans while the rest of the group avert their embarrassed eyes. He is mostly used as a prop and is frequently seen passed out in the background.

And by 'planning', they mean drinking

The group come together to plot and execute the kidnapping of the American ambassador. After researching his habits and patterns they find that he occasionally goes to church and occasionally attends functions but is absolutely religious about attending a local brothel. This is no Nixonian villain. He is a hapless boob who says little aside from “Pity! Pity!” and seems mostly concerned with stuffing his face and shagging prostitutes. Chabrol wonderfully accompanies all of this plotting and sneaking about with a military drum-beat, like something out of The Great Escape or the A-Team.

Not exactly a future member of the Moral Majority then

Once the kidnapping is pulled off, the group flee to a secluded farmhouse and write their manifesto. However, with the group’s intellectual having chosen to sit the heist out, they produce a text that is a hilarious collision of self-aggrandising leftist posturing and slang-filled vulgarity. They talk not of executing their hostage but “simply and modestly” assassinating him. They claim the kidnapping took place in a “whore-house, where his Excellency was getting laid” before going on to talk about “some dead pigs”. They predict a long struggle before the authorities have all been “croaked” and so need to constitute a “nest egg” for the group.

See Minister Run...

Run Minister Run

Aaaand relax

The focus of the film then shifts to the authorities. This section of the film opens brilliantly with the Minister demanding his office send a helicopter to his chateau to pick him up. He descends the staircase as dramatically as Fred Astair, ready to take personal charge of the matter, but in the next scene we see him asleep in bed while a subordinate wakes him up with a cup of coffee. So much for working through the night.

Damn Reds get everywhere...

The Minister sets his assistant to solving the problem who passes the buck to a police inspector in a wonderful scene in which the two men pear round Maoist red lampshades as they try to carry on a conversation. The inspector turns out to be efficient but utterly brutal. With Treuffais chained to a radiator, one policeman asks “have you tried twisting his balls?” the inspector replies indignantly “that’s torture, we don’t do torture… at least not yet”. Unsurprisingly, the group is quickly tracked to their farmhouse and the inspector orders a full assault, caring less for the life of the ambassador than the chance to murder some leftists.

Chabrol clearly wanted his money's worth out of the helicopter

The result is an almost cartoonish blood-bath as the despondent revolutionaries realise that while they might no longer believe in the cause, they might as well leave a historically attractive corpse by heroically dying for it. “Viva Death!” screams Diaz as he runs from the house with a machine gun.

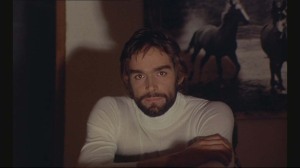

The First and Last Theoretical Contribution by Buenaventura Diaz

Some of the film’s final scenes are quite moving as Diaz comes to terms with what he has lived through. In between footage of the ‘68 Paris riots and chanted slogans, Diaz (now wearing a white polo-neck instead of a black one) speaks directly to the camera of the mistakes he has made. No intellectual and still eager to jockey for position, he rips off the remarks made by Treuffais prior to their falling out : That state terrorism and leftist terrorism are the twin jaws of a steel idiot trap. The state, according to Chabrol, would rather destroy itself than give in to revolutionaries. It would rather deploy terrorism against its own citizens than surrender even an inch to political malcontents. As a result, the political revolutionary has become an almost politically acceptable role… a role that malcontents are forced into allowing the state to brutally repress them. By becoming revolutionaries, the group had fallen into a trap. They gave the state an excuse for killing them. Diaz then travels to Paris in the hope of freeing the sequestered Treuffais, but he foolishly dies in the process, leaving the liberal intellectual as the only survivor, free to talk to the press about what really happened and thereby have some genuine political impact.

“Treuffais” is an interesting choice of name as it is very close to Truffaut, the director who famously took charge when the French film-makers decided to shut down the Cannes festival in ‘68. Chabrol clearly identifies most with the battered, liberalised idealism of Treuffais and by roping Truffaut into it he seems to be suggesting a course of action for his fellow leftist film directors : By taking to the barricades, they would only be making things worse. They can best serve the ultimate goals of the revolution by doing what they were doing at the time, namely thinking about the political climate and sharing their thoughts with a wider public through their words and films.

Title Shot

While Nada’s political content serves as a handy theoretical staging post in Chabrol’s career, it is mainly the film’s personal elements that make it unique. Looking back over Chabrol’s previous films it is hard to imagine that such a man would ever return to the barricades. It is also worth noting that while Nada is seen by many to be an end to Chabrol’s golden period, his next film Une Partie De Plaisir (1975) was just as critical of bourgeois hypocrisy as anything from the early 70s or late 60s. So rather than seeing Nada as marking a political sea-change, it is probably more useful to see it as an admission of personal growth, a recognition of the embourgeoisement that come with age and success. Nada does not mark Chabrol’s break with revolutionary politics, that break was obvious in all the works of his golden period, instead it marks the point at which Chabrol had to admit to himself that he was not the same man he thought he was in 1968.